Social isolation has long been recognized as a significant public health concern, linked to increased risks of mental and physical ailments. However, recent advances in biomedical research have begun to uncover the biological mechanisms that underlie this phenomenon. Scientists are now identifying specific biomarkers that correlate with prolonged social isolation, offering new insights into how loneliness and lack of social connection manifest at a cellular and molecular level.

One of the most striking findings in this field is the discovery that chronic social isolation can trigger measurable changes in immune function. Studies have shown that individuals who experience long-term loneliness often exhibit elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP). These markers, typically associated with the body's response to infection or injury, appear to remain persistently high in socially isolated individuals, suggesting a state of chronic low-grade inflammation. This inflammatory response may explain the well-documented connection between social isolation and increased vulnerability to cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and other inflammation-related conditions.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, our central stress response system, also appears to be significantly affected by social isolation. Research indicates that lonely individuals often display dysregulated cortisol patterns, with either excessive or blunted secretion of this crucial stress hormone. These alterations in HPA axis functioning may contribute to the emotional and cognitive symptoms frequently observed in socially isolated people, including increased anxiety, impaired memory, and difficulty regulating emotions. What makes these findings particularly compelling is that they demonstrate how social experiences can directly influence fundamental biological processes, blurring the traditional boundaries between psychological and physiological health.

At the genetic level, social isolation leaves its mark through changes in gene expression. Cutting-edge research in epigenetics has revealed that prolonged loneliness can lead to differential DNA methylation patterns, particularly in genes involved in immune response and neural plasticity. These epigenetic modifications may serve as molecular scars of social adversity, potentially explaining why the health effects of isolation can persist long after an individual has rejoined social networks. The discovery of such durable biological imprints underscores the profound impact that our social environment has on our basic biology.

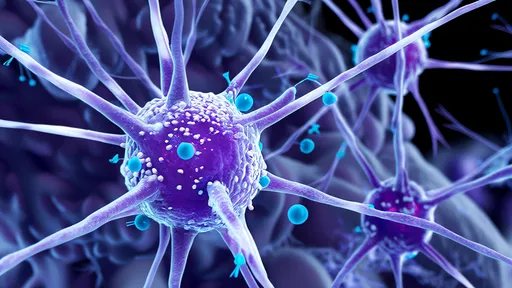

Neuroscience has contributed crucial insights by identifying structural and functional changes in the brains of socially isolated individuals. Neuroimaging studies consistently show reduced volume in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus among those experiencing chronic loneliness, regions critical for decision-making, emotional regulation, and memory formation. Simultaneously, researchers have observed heightened activity in the amygdala, the brain's threat detection center, suggesting that isolated individuals may perceive their social world as more threatening. These neural alterations may create a self-reinforcing cycle where social withdrawal leads to biological changes that make future social engagement increasingly difficult.

The emerging picture from these diverse lines of research suggests that social isolation doesn't merely make us feel lonely—it fundamentally alters our biology in ways that resemble other forms of physical stress and trauma. As scientists continue to map these biological signatures of isolation with increasing precision, we gain not only a deeper understanding of human social needs but also potential targets for intervention. The identification of these biomarkers opens new possibilities for early detection of at-risk individuals and the development of more personalized approaches to addressing the health consequences of social isolation.

Perhaps most importantly, this growing body of research challenges the artificial distinction between mental and physical health, demonstrating how profoundly our social experiences are woven into our biological fabric. As we continue to unravel the complex interplay between social connection and human biology, we may need to reconsider how we approach both healthcare and community building in modern society. The biological markers of social isolation serve as a powerful reminder that human connection isn't just emotionally fulfilling—it's biologically necessary.

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025

By /Jul 21, 2025